By Jeffrey A. Roberts

CFOIC Executive Director

One day in October 1985, the late Neil Westergaard, then The Denver Post’s state Capitol bureau chief, introduced me to the ancient rolltop desk I would use for the next five years as a statehouse reporter for the newspaper.

Rummaging in the drawers and cubby holes, I found rubber bands, paper clips, old “pink book” guides to past legislative sessions and something else — several bottle openers with the Coors logo on them. The openers and an office refrigerator that no longer worked, I learned, were relics of a bygone era that had started to fade away 13 years earlier — now 50 years ago next month — with the passage of Colorado’s Sunshine Law.

Approved by Colorado voters in November 1972, the Sunshine Law ushered in a new era of government transparency in our state, establishing stricter rules for open meetings at the Capitol and providing the basis for the more wide-ranging transparency law that now dictates how all public bodies statewide conduct business.

It also required lobbyists to disclose how much money they spend to influence legislation in Colorado. And that included William R. Spencer, lobbyist for the Colorado Beer Distributors Association.

“When the first quarterly lobbyist reports were filed, I pored over them at the Secretary of State’s office and wrote down everything that looked interesting — including, in the spirit of transparency, how much the state alcohol lobby spent to keep the refrigerator in the press room stocked with beer,” recalled retired Denver Post politics editor Fred Brown, a longtime board member and secretary of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition.

Near the end of a story published on Apr. 15, 1973, Brown reported that Spencer had spent about $140 a month to provide “beer for Statehouse press corps.”

“That pretty much ended the beer distribution,” Brown wrote in an email to CFOIC, “and also had a chilling effect on the afternoon poker games, and on my warm relationships with my colleagues — at least for a while. (And then, when The Post became a morning paper, that definitely put the kibosh on the carefree, boozy afternoons.)”

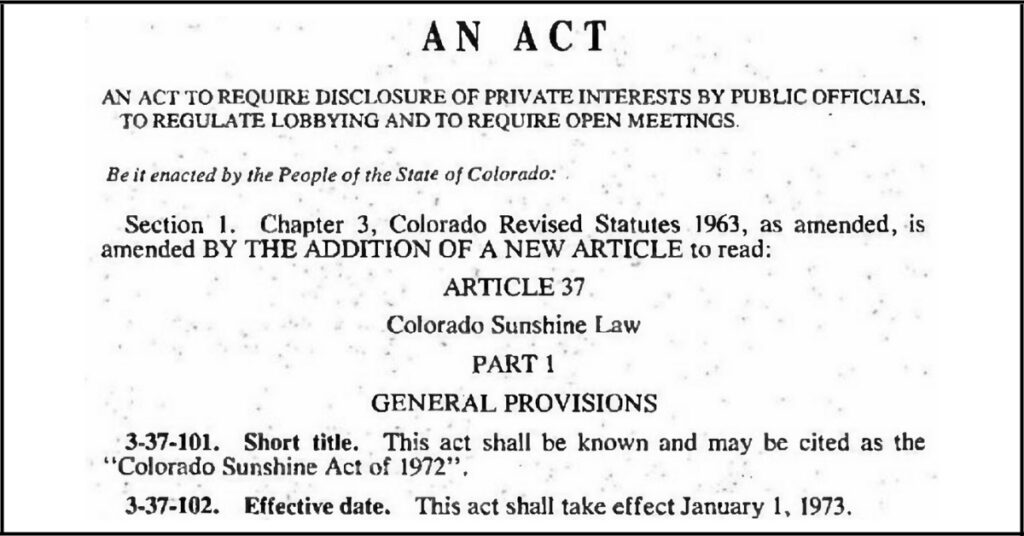

Promoted by Common Cause, the Colorado Sunshine Act of 1972 appeared on the ballot as a citizen-sponsored initiative and passed with 491,073 votes in favor to 325,819 against.

The law had three primary elements: 1) requiring elected state officials and judges to file financial disclosures with the state attorney general’s office; 2) requiring lobbyists to register with the secretary of state’s office and file detailed financial disclosure forms that are “open and readily accessible for public inspection” for five years; and 3) opening meetings of two or more members of any board or other policy-making body of the legislature or state agency “at which any public business is discussed, or at which any formal action is taken.”

The open meetings provision broadly declared state policy to be “that the formation of public policy is public business and may not be conducted in secret.” It mandated that meetings at which a quorum or a majority are in attendance be held “only after full and timely notice to the public.” Minutes had to be “promptly recorded” and open for public inspection. No action taken at a meeting not open to the public would be valid. And “any citizen of this state” could seek an injunction in court to enforce the law.

Plus, according to the 1972 Blue Book analysis of ballot proposals by Legislative Council, state government boards could no longer meet behind closed doors, in executive session, as permitted by a three-paragraph public meetings law enacted in 1963.

The Sunshine Law “is perhaps the most significant single act of legislative reform in Colorado’s history,” wrote Craig Barnes, director of Common Cause’s Colorado Project, in a Dec. 12, 1972, letter to the organization’s founder, John Gardner.

Some state officials were surprised by the Sunshine Law’s passage, according to accounts in The Denver Post and the Rocky Mountain News. “There was substantial opposition …,” says Barnes’ letter, which is kept in the special collections of the Princeton University Library, “but the additional issues on the ballot diverted our opponents’ attention and advertising money.” Noting “cries of anguish” from Gov. John Love, the lieutenant governor, several lawmakers and some judges, he predicted Common Cause would “have to fight extremely hard to hold onto” the Sunshine Law.

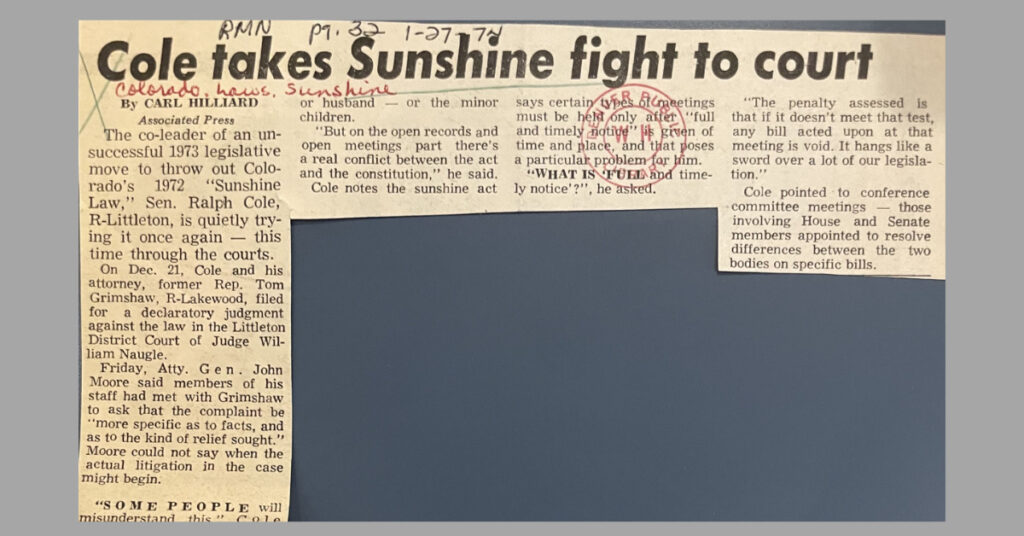

Barnes was right. Sen. Hugh Fowler, a Littleton Republican, sponsored an unsuccessful bill in 1973 to repeal the entire Sunshine Law. What The Post described as “a more moderate approach” from Senate Majority Leader Joe Schieffelin, a Lakewood Republican, and Sen. Ralph Cole, a Littleton Republican, also failed. It would have restored the right of legislators to meet in closed party caucuses and eliminated a requirement that legislators report the financial interests of family members.

State Attorney General John Moore issued a 13-page legal opinion on the eve of the 1973 legislative session, declaring that the open meetings provisions didn’t apply to local governments or school boards. Those provisions also didn’t prevent Love from discussing public business with his staff behind closed doors, nor did they prevent the AG or his assistants from discussing legal strategy in private with state department heads.

But if two or more legislators from the same committee met anywhere to discuss pending business of that committee, the law required them to provide notice. “Any such meetings designed to subvert the intent of the open-meetings law are unlawful,” Moore declared. And the legislature’s political party caucuses could no longer make decisions on floor voting and legislative policy in secret.

The Sunshine Law’s application to party caucuses would be an issue in the courts for the next decade.

In a lawsuit, Cole asserted the law was unconstitutional and shouldn’t be applied to legislative caucuses. It violated his freedom-of-speech rights guaranteed by the First Amendment and the Colorado Constitution, he contended.

But in 1983, the Colorado Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s declaratory judgment that legislative caucus meetings are subject to the law. The open meetings law, the justices wrote, “strikes the proper balance between the public’s right of access to information and a legislator’s right to freedom of speech.” The Court in Cole v. State included in its ruling a statement about the importance of freedom of information that would be quoted in many future court cases, even outside of Colorado:

“A free self-governing people needs full information concerning the activities of its government not only to shape its views of policy and to vote intelligently in elections, but also to compel the state, the agent of the people, to act responsibly and account for its actions.”

The Colorado Supreme Court in 1974 affirmed that the voter-initiated Sunshine Law did not apply to school boards and other political subdivisions of the state. Those were subject to the terse 1963 law, which said that “all meetings of any board, commission, committee, or authority of this state or a political subdivision of the state … are declared to be public meetings and open to the public at all times.” The 1963 law permitted executive sessions “for consideration of documents or testimony given in confidence,” but final policy decisions were not allowed during closed meetings.

A lawsuit challenged the Denver school board’s contention that the 1963 law permitted regular meetings with the superintendent that excluded the public. The Supreme Court justices disagreed with the Denver board in its 1974 ruling, holding that “regardless of whether formal action is taken,” the superintendent conferences were meetings within the meaning of the law and “must be publicly scheduled and opened to the public and news media.”

While that ruling was helpful, open-government proponents wanted a more robust and clearly defined Sunshine Law that would apply to both state and local public bodies. The 1963 law had “no definition of meeting, utter vagueness on when and how local public bodies may go into executive session, no requirement of notice or minutes,” said Tom Kelley, a longtime CFOIC board member and past president.

In 1991, as attorney for the Colorado Press Association, Kelley drafted the comprehensive, two-tiered legislation that became today’s Colorado Open Meetings Law. And over the past two decades, amendments and court rulings have generally made the law stronger and ensured compliance by governmental bodies.

The revised provisions mandating access to meetings of all “public bodies” still appear in the Colorado Revised Statutes alongside the public official-disclosure and lobbyist-regulation provisions, in an article titled “The Colorado Sunshine Act of 1972.”

Related from 2018: Fifty years of the Colorado Open Records Act: ‘Terrible, terrible piece of legislation!’

Follow the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition on Twitter @CoFOIC. Like CFOIC’s Facebook page. Do you appreciate the information and resources provided by CFOIC? Please consider making a tax-deductible donation.